Long hair, inverted feet, hungry for blood, seeking revenge- these attributes are used in South Asian folklores to paint a scary description of the ‘churail’, or demon woman. The Western web series obsession with witches, covens, and black magic and now Indian web series inspired me to get over my childhood fear and explore the provenance of brown witches ‘Churail’. I discovered the lore behind who became a churail was not only fascinating, it is also pretty feminist.

It turns out that churails are described as women who died during pregnancy or childbirth or at the hands of mistreatment by their husbands or in-laws. They haunt those who abused them or target young men at random, luring them high into mountains or deep into the forest, seducing them while entrapping their youth and sending them back down as old, weakened men.

This discovery shook me: not only were churails badass af, but the target of their ire was also typically men. Most interestingly, these origin stories seemed to serve the function of protecting. And while there’s no doubt a vitriolic strain of misogyny that exists in South Asia, my discovery of this folklore was part of a growing body of evidence of ancient, homegrown feminism.

Reporting for Fountain Ink, Indian journalist Monica Jha found between 2002 and 2014, the National Crime Records Bureau showed across the country 2,290 people—mostly women—were killed in circumstances that imply witch-hunting was the motive. In reality, as Jha and others have reported, these cases are often linked to forcing women off their land.

And there are other circumstances in which women are targeted: when they suffer from mental health issues or blamed for bad luck befalling the family, like a sudden illness or death.

Little girls in India hear the term a lot, When your braids have opened up, you are a ‘churail’. When you speak loudly, you are a ‘churail’. When you are not listening to someone, you are a ‘churail’. The most notorious, quarrelsome and troublesome woman in a family, or one gifted with the longest broadest sharpest tongue in a family. So whenever a person who is not understood, who is not accepted, who does not fit any box, becomes a churail.

Most commonly, the word churail is weaponized as an insult. For director Asim Abbasi, the term represented qualities that were seen as undesirable in a woman: courage, aggression, intelligence, sexual liberation. Growing up in Karachi, he heard the world hurled at women that did “anything beyond the narrow definition of a conformist woman with someone who sits at home and blithely obeys.”

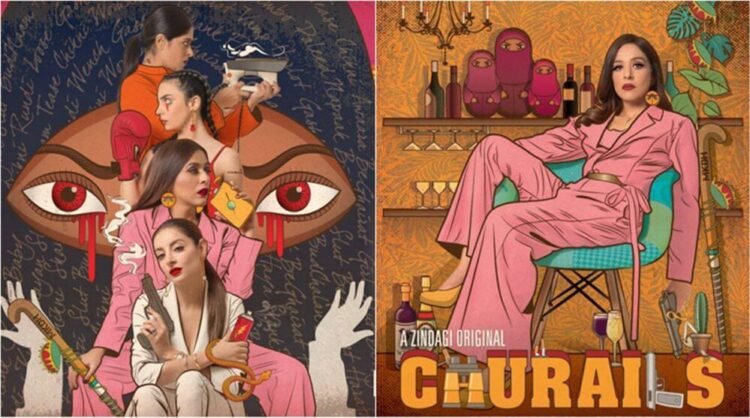

Zee Entertainment, which was looking to relaunch its channel Zindagi TV contracted the Director and writer Asim Abbasi, who has acquired a loyal fanbase after Cake was picked up by Netflix in 2019. Zindagi brought acclaimed Pakistani and Turkish television shows into Indian homes but suspended operations after the 2016 terrorist attack on an Indian Army camp in Uri in 2016.

Zindagi has now been reborn on the Zee5 streaming platform, where it will deliver 1000+ hours of curated and created content through fresh new shows which will be thought-provoking.

In Asim Abbasi’s feisty and furious web series Churails, a ten-episode web series brims over with feisty, feminist, fast-paced fun. ‘Mard ko dard hoga’, they promise. And that’s exactly what they delivered. churails exposed what is rotten in society by a Karachi-based boutique selling burqas: the garment obscuring their intent and faces. It’s called Halal Designs store in Karachi is actually a front for the clandestine Churails detective agency spearheaded by a group of socialist in order to operate as unlicensed dispensers of justice in plain sight.

Meet the foursome which forms the core of the group. Stung to the quick by her husband, and with memories of a previous misdemeanour returning to haunt her, Sara (Sarwat Gilani Mirza), an out of practice lawyer, enlists her childhood friend Jugnu (Yasra Rizvi) in her campaign for revenge. Jugnu, a frequently-imbibing high profile wedding planner whose most recent job has ended in disaster, is a willing conspirator. Fate brings two other women from the other end of the economic divide to them. One is Zubaida (Mehar Bano), a student whose clothes conceal boxing shorts, wants to break free from her traditional family. She wants to flirt with her boyfriend when she is not boxing, which, she says, gives her joy. The other woman doesn’t bother to hide her identity. Batool (Nimra Bucha) is a proud convict, having served a long prison sentence for murdering her abusive husband.

The quirky quartet, aided by Zubaida’s hacker boyfriend Shams (Kashif Hussain) and Jugnu’s assistant Dilbar (Sarmed Aftab Jadraan), recruit more women to their cause. This rebellion gang also include a prostitute, a pair of ex-cons and a trans woman. Business is swift and lucrative, but the cracks appear soon enough. Why are we only helping rich housewives when our goal is to liberate all women, Zubaida wonders.

Abbasi here turns the stereotype of suspicious women on its head by showcasing the prevalence of dubious husbands. Till the fourth episode — each almost 55-minutes long — the plot resembles feminist wish-fulfilment: women rescuing other women while the line between the oppressor and oppressed remains intact. Reputed mansions cases open up trails that take the series from neighbourhood vigilantism to an all-out attack on patriarchy itself. Churails then explores the cost women have to bear to not be but become vigilantes: unlearning everything they knew before, even their own words. The rot that the titular “witches” end up exposing runs deep. Child abuse, domestic violence, the trafficking of women, drug abuse, even fairness obsession – Churails rampages down the list. Their identification as churails is both a tease for the male gaze — trained to view transgressive women as witches — and an unsaid sis code for the female where the term is a covert indicator of a saviour.

Each actor has been cast well and has poured their heart and soul into their parts. Though they’re not known to many of us, each one slowly but surely grabs our attention and holds it tight. On the negative side, most of the actors in Churails speak English with a curious westernised accent and some cuss words which is very unusual of Pakistani drama. It is quite distracting and rankles in the otherwise flawlessly performed acts. Churails has some terrific songs that boast great lyrics. The soundtrack adds an upbeat and galvanising tempo to the narrative. Mo Azmi’s cinematography is brilliant.

In case of a feminist vigilante drama, the danger is quantified in terms of menacing men as redemption hinges on revenge. ( Stree, Bulbul, A Girl Who Walks Home Alone At Night ). But they both merge in the genre’s abiding theme: complete dependence on the vigilante to decide for the rest and on their understanding of right and wrong.

But Abbasi is not scrutinising female vigilantes here. Rather, he is critiquing the genre that presupposes a liberator as the ultimate decider and to be in a position to operate as the same. What he is doing, in fact, is using the genre of female vigilantism as a veil to depict the insidious impact of patriarchy that leaves none untouched, not even vanguards. He is striking at its biggest achievement: conditioning of women.

Also read: Bulbbul Review: Child Marriage, Social Truths, Suspense

[zombify_post]